BY BENJAMIN WILSON

The Central African Republic (CAR) has experienced long-term, widespread insecurity that has contributed to high levels of internal displacement and refugee flows. Although such insecurity intensified in the early-to-mid 2010s, a more stable government has helped the nation improve over the past few years. The Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index (FSI) scores illustrate the nation’s positive, if inconsistent, displacement trends.

CAR has historically been rated as an impoverished, fragile, and unstable country[1]. Since its independence in 1960, CAR has experienced recurrent coups and violence. Consequently, it has also experienced recurring cycles of population displacement.

For example, the March 2003 coup internally displaced about 200,000 CAR residents. Few returned to their prior residencies in the following months due to fear of revenge from new authorities or lawlessness[2]. In 2005, about 212,000 CAR residents were internally displaced due to political violence, banditry, and conflict between armed forces and rebel groups. In 2006, ongoing banditry and violence displaced an additional 150,000[3].

Spread widely across both urban and rural landscapes, internally displaced persons (IDPs) often had little or no access to clean water, healthcare, nutrition, basic security, and proper shelter due to the lack of aid services available to IDPs. The arrival of rebel groups, such as the Lord’s Resistance Army in 2009, displaced at least 18,000 more Central African residents. Between 2002 and 2010, four out of five people in CAR fled their homes[4]. In 2013, another coup forced 640,000 people to flee the country and internally displaced another 630,000[5]. Between its first rating in 2006 and the 2013 coup, the FSI index score for CAR slowly rose from 7.7 to 10.0, indicating the highest level of fragility[6].

In 2016, a new presidential administration failed to bring greater stability to the country. As fighting between warring factions grew, the government lacked control outside of the capital, Bangui, allowing conflict, poverty, and lawlessness to drive Central Africans out of the country, increasing CAR’s refugee count. In addition, more Central African residents were displaced internally[7]. A February 2019 agreement for peace between the government and 14 armed groups showed potential, allowing some IDPs and refugees to return[8], but by June 2020, the number of IDPs in CAR was back to over 650,000.

CAR’s score in the “Refugees and IDPs” category of the FSI remained at 10.0, the highest possible score, until 2020. In 2020, CAR experienced election and post-election conflicts that displaced 200,000 people[9]. However, after March 2021, refugees from CAR began to return, as the results of the 2020-21 elections helped stabilize CAR by increasing constitutional order[10].

CAR’s “IDP and Refugee” score does remain high today as conflicts flare between the Central African Armed Forces (FACA) and non-state armed groups[11]. In 2022, it ranked the fourth-lowest in the world on the Human Development Index[12] and the fifth most fragile on the FSI[13]. As a result of the recent elections, however, peace agreements and greater stability have allowed for more refugees to return to the country and IDPs to resettle; consequently, their fragility score improved and they dropped to 8th most fragile in the 2023 FSI.

The internal displacement situation in CAR has been severe, as 1.9 million Central Africans, over a third of the nation’s population, have been displaced from their homes at some point over the last 50 years[14]. An estimated 738,000 people, half of whom are children, are currently internally displaced within the country[15].

CAR generally serves as a source of refugees rather than a destination country. In August 2021, there were about 709,000 refugees originally from CAR, primarily hosted in Cameroon, the DRC, Sudan, Congo, and South Sudan[16]. Many reside in remote, hard-to-reach areas without shelter and face food shortages as well as other humanitarian struggles, For example, the tens of thousands of Central African refugees who left for the DRC in 2020 and 2021 relied on the Ubangi River for water, leading to malaria, respiratory tract infections, and diarrhea[17]. Because CAR relies on the supply lines of its neighbors, it was significantly impacted by the supply chain disruption due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Price increases further impoverished vulnerable populations, forcing families to send their children to work and increasing community-level violence, including GBV[18].

CAR only hosts 9,181 refugees from other countries, including DRC, South Sudan, Chad, Sudan, and Rwanda. As noted, CAR is not frequently sought as a destination country and has been criticized for inadequate victim services, unlawful recruitment of children, and the national assembly’s failure to finalize anti-trafficking legislation[19]. Perpetrators of trafficking are often merchants, herders, and armed groups[20].

As with most countries with agriculture-based economies, Central Africans voluntarily migrate within the country for economic opportunities. The majority of such internal migration in CAR is rural-to-urban, as people are often attracted by educational opportunities, such as the nation’s only university in Bangui. Economic opportunities attract migrants, but the hardship and unemployment of the city have also driven some migrants to return to rural areas. Seasonal rural-to-rural migration is also noted due to the presence of pastoral nomadic groups. Internal migrants often end up working in natural-resource industries, such as mining and agriculture[21].

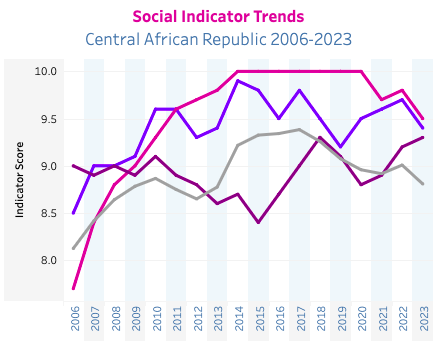

Despite the high levels of displacement across several groups in CAR, the country is improving. Post-election stability increased the number of IDPs able to return to their homes in 2022[22]. As shown in Figure 1, the FSI’s ratings in the Social Indicator pillar are mostly trending towards decreasing fragility. If CAR can continue to strengthen its governmental institutions and reduce violence, there is hope that this trend toward greater stability will endure.

[1] “Central African Republic Refugee Crisis: USA FOR UNHCR.” Central African Republic Refugee Crisis | USA for UNHCR. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/car/

[2] “200,000 Displaced by Coup in Central African Republic Face Serious Food Crisis – Central African Republic.” ReliefWeb, October 28, 2003. https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/200000-displaced-coup-central-african-republic-face-serious-food

[3] “Migration Dimensions of the Crisis in the Central African Republic : Short, Medium and Long-Term Considerations – Central African Republic.” ReliefWeb, September 15, 2014. https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/migration-dimensions-crisis-central-african-republic-short-medium

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Central African Republic Refugee Crisis: USA FOR UNHCR.” Central African Republic Refugee Crisis | USA for UNHCR. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/car/.

[6] “Country Dashboard.” Fragile States Index. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/.

[7] “Conflict in the Central African Republic | Global Conflict Tracker.” Council on Foreign Relations, June 7, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-central-african-republic

[8] “Central African Republic.” Migrants & Refugees Section. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/central-african-republic/.

[9] “Central African Republic Refugee Crisis: USA FOR UNHCR.” Central African Republic Refugee Crisis | USA for UNHCR. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/car/.

[10] “Situation Reports.” Global Focus. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://reporting.unhcr.org/situation-reporting?sitcode=116.

[11] Ibid.

[12] United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2021/22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World. New York, NY: UN Headquarters, 2022.

[13] “Country Dashboard.” Fragile States Index. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/.

[14] “Central African Republic Refugee Crisis: USA FOR UNHCR.” Central African Republic Refugee Crisis | USA for UNHCR. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/car/.

[15] “Central African Republic.” Migrants & Refugees Section. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/central-african-republic/.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Conditions Dire as Car Displacement Tops 200,000.” USA for UNHCR. The Un Refugee Agency, February 1, 2021. https://www.unrefugees.org/news/conditions-dire-as-car-displacement-tops-200-000/.

[18] United Nations, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Global Report 2020. New York, NY: UN Headquarters, 2020.

[19] “Central African Republic – United States Department of State.” U.S. Department of State, March 29, 2023. https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/central-african-republic.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Central African Republic.” Migrants & Refugees Section. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/central-african-republic/.

[22] United Nations, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Global Report 2020. New York, NY: UN Headquarters, 2020.