BY LANGDON OGBURN

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the 2011 NATO-led intervention in Libya—a decade that has included terrorist control, degraded civil services, and a civil war characterized by allegations of war crimes within the country. Libya rated as the Fragile State Index’s “most-worsened” country for the 2010 decade. Recent Libyan history offers a clear lesson—the international community ought to aid fragile states through the post-conflict period of humanitarian intervention. This responsibility is compounded when international actors play a role in creating difficult postbellum circumstances.

The response of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s regime to the Arab Spring posed a very real threat to Libya’s population. In March 2011, shortly after the beginning of the Libyan uprising, Col. Gaddafi released a message stating “we will come. House by house, room by room,” and that “only those who laid down their arms would “be spared the vengeance awaiting rats and dogs.” The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1973 in response to this threat, which mandated the international community “to take all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civilians. This was the first internationally sanctioned military operationalization of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P)—an international norm that advocates for intervention in cases of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) took charge of this mandate.

The international understanding of the term “all necessary measures” at the time of passing of the resolution did not include regime change. Yet, in April 2011, US President Barrack Obama, UK Prime Minister David Cameron, and French President Nicolas Sarkozy released a joint statement that it was impossible to protect Libyan civilians without this action. NATO forces assisted Libyan rebels through weakening the Gaddafi regime’s military forces, and by maintaining a no-fly zone that nullified the Libyan government’s airforce. On the morning of August 20, 2011, French airstrikes targeted some of the dictator’s last remaining military assets before Gaddafi was executed. Following the execution, there was an immediate, mass exodus of international actors from Libya.

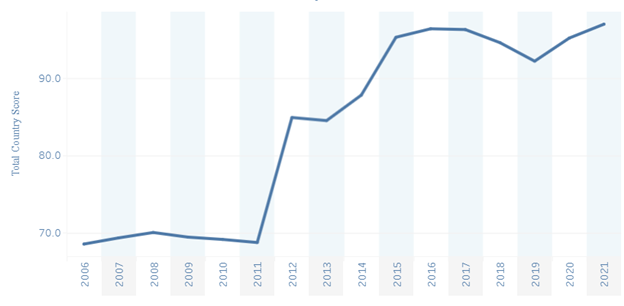

Figure 1. Libya’s Overall Trend on the Fragile State Index, 2006-2021

Libya’s scores on the Fragile State Index encapsulate the decade of instability that has followed the Gaddafi Regime’s deposition. From 2011 to 2021, Libya has seen an increase of 28.3 points in its fragility score, from 68.7 to 97.0, and a 94-place increase of its ranking, from 111th to 17th most fragile. Every single indicator of state fragility except for economic inequality is higher than in 2011. Most notably, this includes a 3.7 increase in Security Apparatus, a 5.0 increase in Economic, and a 3.1 increase in Public Services indicator scores.

This is not to say that Libya would be better off today if the Gaddafi Regime had remained in power. As USAID Director Samantha Power – then-National Security Council member and a key advocate for intervention – pointed out in an interview, Libyan citizens’ quality of life would not have been the same as the pre-2011 standards had Gaddafi stayed in power. Yet, a deeper inspection of Libya’s FSI scores indicates something far more tenable when placed in historical context. In 2012 and 2013, a new, fragile Libyan state reached a crossroads in state stability. Due in no small part to a lack of international support, the Libyan state would prove unable to overcome its dramatic, post-war circumstances, thus beginning a journey toward ever-increasing fragility.

In the aftermath of the Gaddafi deposition, Libyan civil leaders created an egalitarian constitution that guaranteed political representation through a parliamentary form of government. In just one example of how the liberal ideas of the Arab Spring influenced the new government, provisions were set to guarantee women’s representation in the general assembly. Female candidates won 33 of the general assembly’s 200 seats—a women’s representation percentage equivalent to that of both bodies of US Congress at the time. In the general assembly’s first, relatively peaceful, election over 60% of the eligible population participated.

Despite the establishment of a progressive and publicly-supported government, however, it was clear that the Libyan people had a challenging road ahead of them. After the collapse of the dictator’s regime, few strong governmental institutions and individuals with experience in governance remained in the country. As a result, threats to the new state’s legitimacy were rarely met with effective public policy.

Among these threats were the 60+ independent militia groups vying for power with access to a total quantity of weapons equivalent to three times the Libyan population. International actors had once supported these militia groups, and had supplied them with the arms they now used against the fledgling, publicly supported Libyan government. Incapable of demobilizing these groups, the new Libyan security sector often attempted to incorporate them into the public security apparatus. Yet, this method proved ineffective: by 2013, the Libyan security sector had effectively lost control to increasingly independent militia groups over vast parts of the country.

The international community helped topple an authoritarian and abusive regime which had nevertheless provided a measure of stability. Doing so enhanced the military capacity of militia groups that threatened the new government’s legitimacy. Helping overthrow the abusive regime did not alleviate the international community’s responsibility toward helping the new government cope with the circumstances it contributed to creating. Although the US, a very influential member of NATO, seemed to understand R2P differently, the Obama administration clarified that nation-building was not part of the intervention plan in Libya.

The idea of moral responsibility toward state assistance following intervention is not new. The 2001 Report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty—where R2P was first recognized as an international principle—defined a “Responsibility to Rebuild” as an essential part of R2P. The Libyan intervention highlights that this aspect of R2P must be viewed as a non-optional aspect of humanitarian intervention. Without a continued commitment to the responsibility to rebuild after an R2P operation, the intent of securing civilian rights cannot be guaranteed in the long term.

Following the removal of Gaddafi, the international community could have taken any number of actions that did not include military occupation, which was anathema to the Libyan population. During the early days of the fledgling post-Gaddafi government, which were frought with danger and therefore particularly formative, international actors could have worked through international development groups to build institutional capacity, support Libyan-led security sector reform, or provide training opportunities for new public leaders, among many other options. Yet, when the new government needed support the most, it received none. It would not be until 2014, well into Libya’s path to state failure, that the US—the primary supporter of the Libyan intervention—would suggest providing aid to help Libya’s security situation.

It might be impossible to determine whether Libya would be better today if Gaddafi had never been deposed. However, the international community could have taken any number of actions to help the nascent Libyan government overcome circumstances that impacted the country’s fragility. It is possible that if the international community had acted to aid the Libyan government immediately following the intervention, it would not be experiencing the levels of instability and fragility that it endures today.

The Libyan intervention itself was premised on a responsibility held by the international community toward the rights and wellbeing of the Libyan people and acknowledged by the R2P. The decade following the Libyan intervention has shown that this responsibility should not have ended with the conflict. Through aiding Libya to recover from its difficult, post-conflict circumstances, long-term safeguarding of the rights of the Libyan people may have been achievable. The international community must learn from the Libyan intervention the importance of helping states after intervention takes place.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the Department of the Army or Department of Defense.

Posts on Deconflictions represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of FFP.