BY HANNAH BLYTH

Since the end of an almost two-decades long civil war that began in 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) has provided relative political stability and enabled strong economic development. Though an inter-state conflict with Eritrea over disputed territory flared in 1998-2000, since the ceasefire was declared between the two countries in December 2000, Ethiopia has been on a path of strong fiscal growth and has become an increasingly respected player within the international community. Ethiopia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has risen from US$8.2 billion in 2000, to an impressive US$61.5 billion in 2015 – coinciding with major injections of foreign capital from development partners. Looking past these golden dollar sign headlines, however, there are signals that deep social and political fissures have the potential to set the country back on a path to conflict.

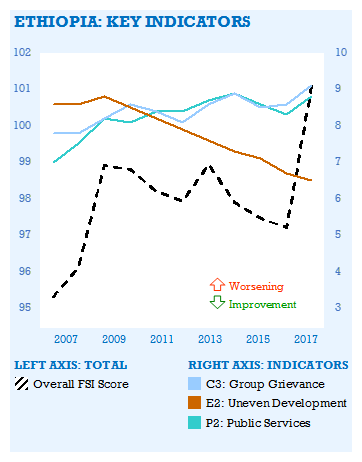

Ethiopia’s overall Fragile States Index (FSI) score has been incrementally worsening over the past decade, moving from 95.3 in 2007, to a score of 101.1 in this year’s 2017 index, with Ethiopia — along with Mexico — being the most-worsened country over the past year.

Ethiopia’s overall Fragile States Index (FSI) score has been incrementally worsening over the past decade, moving from 95.3 in 2007, to a score of 101.1 in this year’s 2017 index, with Ethiopia — along with Mexico — being the most-worsened country over the past year.

Some of this can be attributed to External Intervention, with its FSI score moving from 6.7 in 2007 to 8.7 in 2017, making it Ethiopia’s most worsened indicator overall for the decade. In 2000, Ethiopia received US$687.8 million in Official Development Assistance (ODA).1 By 2015, it had risen to over four times this with US$3.23 billion in ODA, mostly from the U.S., World Bank and European partners focused on social infrastructure and humanitarian aid.2 While this suggests low capacity of the state to plan and respond to natural disasters without external aid, arguably this development funding has also been crucial in stimulating the rapid economic trajectory of the country. Ethiopia’s economic indicators have both made improvements over the past decade, with FSI scores for Uneven Economic Development shifting from 8.6 in 2007 to 6.5 in 2017, and Poverty & Economic Decline from 8.0 in 2007 to 7.0 in 2017. While the economic trajectory tells one part of the story, the gap in public services between the urban areas such as bustling Addis Ababa, and rural areas – where 81% of the population still live3 — hint at growing disparities. The country’s Public Services score in the FSI has worsened from 7.0 in 2007 to 8.8 in 2017 – much of this is due to poor access to internet and communications, as well as limited improvements in water and sanitation facilities within the county.4 Health infrastructure also remains weak in many areas, with only 15% of births attended by a skilled health professional, and just 0.02 Doctors per 1,000 people within the populous country.5 The highly centralized nature of the EPRDF means that the nine ethno-linguistic regions of Ethiopia have limited power and resources for provision of public services. The military also plays an active role in reinforcing the centralized development agenda – with much of the county’s development driven via the military-controlled conglomerate Metals, Engineering Corporation (METEC). As a 2016 report by Dutch think tank Clingendael surmised, this increases risks of “corruption, nepotism and inefficient resource allocation,”6 all of which can increase the disconnect between development and rural populations.

Compounding these growing disparities between rural populations and economic growth are complex political and ethnic tensions. The historical influence of the Tigray ethnic group – which accounts for about 6% of the population – has been evident since the Ethiopian empire, and reinforced after the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) defeated the Ethiopian government in 1991. The TPLF transitioned into the multi-party EPRDF, though Tigray elites are perceived to still hold significant political power within the essentially one-party state. Military leadership has also been dominated by Tigrayans,7 which makes perceptions of Tigray influence within the state apparatus all the more unpalatable to populations that feel increasingly excluded.

It is amidst this climate that major protests and violence have erupted against the government in Oromia and Amhara regions – home to the two largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia. Beginning in November 2015, Oromians began protesting the government’s planned expansion of the capital Addis Ababa into Oromia. Spiraling into a broader fight for increased political freedoms, representation and economic and land rights, the protests were met with brutal crackdowns by public security forces. Reflecting these dynamic factors, Ethiopia has seen negative spikes in its FSI score from 2016 to 2017 in Group Grievance, Human Rights and Rule of Law and State Legitimacy. Human Rights Watch suggests that more than 500 people have been killed during the government demonstrations in 2016, as well as reported incidents of arbitrary detention, torture, and media repression aided by the government’s State of Emergency declared in October 2016.8

While ethnicity remains a politicized factor within Ethiopia – and salient driver of group grievance for populations who feel excluded – it is useful to remember that conflict and violence operates within a system. Issues related to land tenure, access to resources, and economic exclusion can also be contributing drivers for the current insecurity. This is also complicated by ongoing demographic pressures resulting from floods and drought, and flows of refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) from natural disasters, the effects of climate change, and neighboring countries’ insecurity. Indeed, the FSI score for Refugees & IDPs has steadily worsened over the past decade from 7.9 in 2007 to 9.3 in 2017.

Ethiopia’s centralized government control has served it well for economic growth and rebuilding after the civil war and conflict with Eritrea – as well as maintaining control of the security apparatus amidst neighboring conflicts and regional instability. However, as worsening FSI scores show through both a longer-term trajectory, and recent 2017 spikes, the country must change course to strengthen internal social and economic resiliency. The recent spate of protests and insecurity in areas such as Oromia and Amhara demonstrate the need for political reform – both in perceptions of ethnic elite power – and in more meaningful political representation of each region. This will help to address the disparities in public service provisions that are adding to group grievance and feelings of exclusion. A less centralized approach will also help build governance capacities at regional and local levels – which will support rural development, and provide a chance for better targeted planning and response for natural disasters. As the fourth largest ODA recipient country in 2015, international partners should also continue to play an encouraging role in Ethiopia’s reform, including expansion of civil liberties which will reduce group grievance and increase the perceived legitimacy of the state.

Through addressing the conflict risks and structural vulnerabilities within the country, Ethiopia has a chance to continue a path of peaceful prosperity and even greater economic growth and development.

ENDNOTES

1. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ALLD.CD

2. http://www.oecd.org/statistics/datalab/oda-recipient-sector.htm

3. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS

4. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.ACSN.RU; http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.H2O.SAFE.RU.ZS

5. http://datatopics.worldbank.org/hnp/

6. https://www.clingendael.nl/pub/2016/power_politics_and_security_in_ethiopia/executive_summary/

7. Regime Change and Succession Politics in Africa; Jan Zanhorik (2009) https://books.google.com/books?id=Gow8JDgeZSoC

8. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/ethiopia