BY DANIEL GANZ

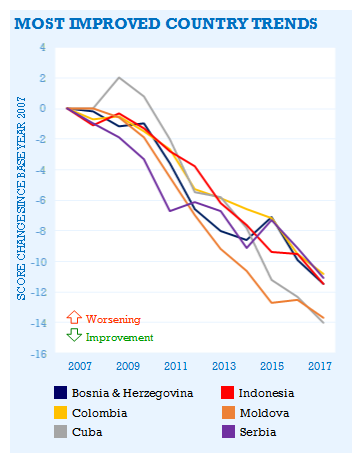

The most fragile — and the most worsened — countries tend to attract the most attention in the Fragile States Index (FSI). However, the reality is that the majority of countries are improving based on the FSI’s trends, and a number of countries have made considerable progress in the past decade based on their FSI scores. These examples demonstrate that a long-term commitment to peace and reconciliation, poverty reduction, and economic growth collectively contributes to a government’s legitimization, and ultimately, the stability of its country.

In the first Fragile States Index in 2005 (albeit with a more limited sample of only 76 countries), Colombia ranked 14th; now, in 2017, Colombia ranks 69th. Even in the past decade, the difference is remarkable — in 2008, Ingrid Betancourt, anti-corruption activist and politician, was rescued by the Colombian army after being held hostage by rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) movement for six years. Increasing concern that hostage-taking would continue served as an important catalyst to the next series of peace talks held between the Government of Colombia and the FARC. Four years later, in 2012, a ceasefire was negotiated and in 2014, the government and FARC began a large-scale crop substitution program, promoting the growth of licit crops to sustain the countryside’s livelihoods rather than its continued dependency on illicit drugs. In 2016, the government and FARC rebels came to peace deal, that after getting rejected by voters, was revised and ratified, ending the 52-year conflict. As a relatively developed country with a well-educated population and relative political stability, Colombia was certainly held back by the conflict. Now, as that conflict draws to a close, Colombia’s score has rapidly improved, demonstrating very clearly the severe cost that accompanies conflict.

In the first Fragile States Index in 2005 (albeit with a more limited sample of only 76 countries), Colombia ranked 14th; now, in 2017, Colombia ranks 69th. Even in the past decade, the difference is remarkable — in 2008, Ingrid Betancourt, anti-corruption activist and politician, was rescued by the Colombian army after being held hostage by rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) movement for six years. Increasing concern that hostage-taking would continue served as an important catalyst to the next series of peace talks held between the Government of Colombia and the FARC. Four years later, in 2012, a ceasefire was negotiated and in 2014, the government and FARC began a large-scale crop substitution program, promoting the growth of licit crops to sustain the countryside’s livelihoods rather than its continued dependency on illicit drugs. In 2016, the government and FARC rebels came to peace deal, that after getting rejected by voters, was revised and ratified, ending the 52-year conflict. As a relatively developed country with a well-educated population and relative political stability, Colombia was certainly held back by the conflict. Now, as that conflict draws to a close, Colombia’s score has rapidly improved, demonstrating very clearly the severe cost that accompanies conflict.

Whereas Colombia’s progress was fueled largely by peacebuilding efforts, Moldova’s move towards increased stability results from its attention to political and institutional reforms and the economy. In 2014, the country, and its citizens, began to experience rapid improvement when it signed its association agreement with the EU. At the same time, a World Bank Group report found that Moldova’s regulatory reforms made it easier for local entrepreneurs to do business. For example, Moldova was ranked 92nd out of 178 countries in the World Bank’s Doing Business report in 2008; ten years later, that ranking has been cut in half, with Moldova coming in at #47. Moldova also made significant democratic reforms, such as the constitutional court’s ruling in 2016 that the popular vote will now determine the results of presidential elections rather than parliamentary vote.

Nearly ten years ago, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU was put on hold, citing the country’s political, institutional, and economic setbacks at the time. Since then, the country has fought hard to regain its EU standing yet it was not until seven years later, in March 2015, that the EU and Bosnia and Herzegovina returned to the Agreement. One year after that, Bosnia and Herzegovina submitted its application to join the EU. It was later accepted, provided that the country continue its reforms in the areas of rule of law and governance. In 2016, cultural and political gains gave the country reason to celebrate and heal wherein former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic was convicted for war crimes and genocide, ending a 20-year effort to hold him accountable for the atrocities in the 1992-1995 war.

Indonesia’s last decade was marked by the government’s retaliatory crackdown on Islamic extremists and a flexing of its economic muscles, gradually becoming the tenth largest economy in the world in terms of purchasing power. Indonesia’s campaign against those responsible for terrorist attacks, including the suicide bombings at the JW Marriott and Ritz-Carlton hotels, culminated with the 2012 conviction of Umar Patek for his role in the 2002 Bali attacks, ending a decade’s long investigation into the bombings. During this same period, Indonesia’s inauguration as a G20 member in 2008 formally recognized the country’s growing influence in the global economy. As the world’s fourth most populous nation, Indonesia’s commitment to institutional reforms led to historic lows of its poverty rate to 10.9% and a 66% increase of GDP per capita from US$2,168 (2008) to US$3,603 (2016).

Serbia’s place amongst FSI’s most improved countries over the last decade began on a most inauspicious note, starting with the repercussions resulting from its role in the region’s wars in the last 20 years. In 2008, this started with Kosovo’s declaration of independence in February and ended with the arrests of Radovan Karadzic and police chief Stojan Zupljanin. Whether these events served as a catalyst or not, Serbia’s increased willingness and acknowledgement of its role in the Bosnian and Kosovar conflicts began the country’s long road back to political and economic stability. The Progressive Party was growing in influence and following 2013 Brussels Agreement, Serbia’s efforts to join the EU were back on track. The government’s institutional reforms (e.g. streamlining its business registration process) were also beginning to bear fruit, with Serbia’ ranking in the 2016 World Bank’s Doing Business report (54th) representing a dramatic improvement from a ranking of 116th a decade ago. Further economic progress was noticeable in 2016 with an increase in domestic investment and a decrease in its unemployment rate from 17.7% in 2015 to 13% in 2016.

Since his rise to power ten years ago, Cuba’s leader Raul Castro has accomplished more to improve Cuba-U.S. relations, usher in modern technologies, and stimulate its economy than his brother had done in the previous half a century. For example, in 2008, restrictions on owning mobile phones were lifted. In 2009, U.S. President Obama lifted restrictions on Cuban Americans to visit and allow them to send money to Cuba. In August 2011, President Raul Castro’s plan to enact economic reforms such as owning small businesses and reducing bureaucracy was approved by the National Assembly. With the 2013 re-election of President Raul Castro, Cuba was removed from the list of being a sponsor to terrorism, and banking ties between the two countries quickly followed. These incremental changes in Cuba’s political, economic, and social landscapes contributed to the historic events of 2016 that included the US easing trade restrictions to Cuba, diplomatic ties between the EU and Cuba were established, and President Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the country in 88 years.

In the face of terrorist attacks and war, extreme poverty, and economic stagnation, these six countries established foundations for recovery that they are now benefitting from in 2016, as noted above. It is certainly a credit to each country’s long-term commitment and resolve to improve the quality of life for its citizens.

While these same six countries still face significant obstacles – ethnic tensions are on the rise, government reforms have fallen short of expectations, and corruption levels threaten the legitimacy of state institutions – they all have their own roadmaps, ones that led to successes in the recent past.