BY J.J. MESSNER

As the civil war in Syria enters its sixth year, its effects continue to wreak havoc not only on its own war-ravaged population, but also upon countries farther afield. In the 2016 Fragile States Index, Syria was again one of the most worsened countries year-on-year, catapulting them into the list of the top ten most fragile countries on the planet.

As the civil war in Syria enters its sixth year, its effects continue to wreak havoc not only on its own war-ravaged population, but also upon countries farther afield. In the 2016 Fragile States Index, Syria was again one of the most worsened countries year-on-year, catapulting them into the list of the top ten most fragile countries on the planet.

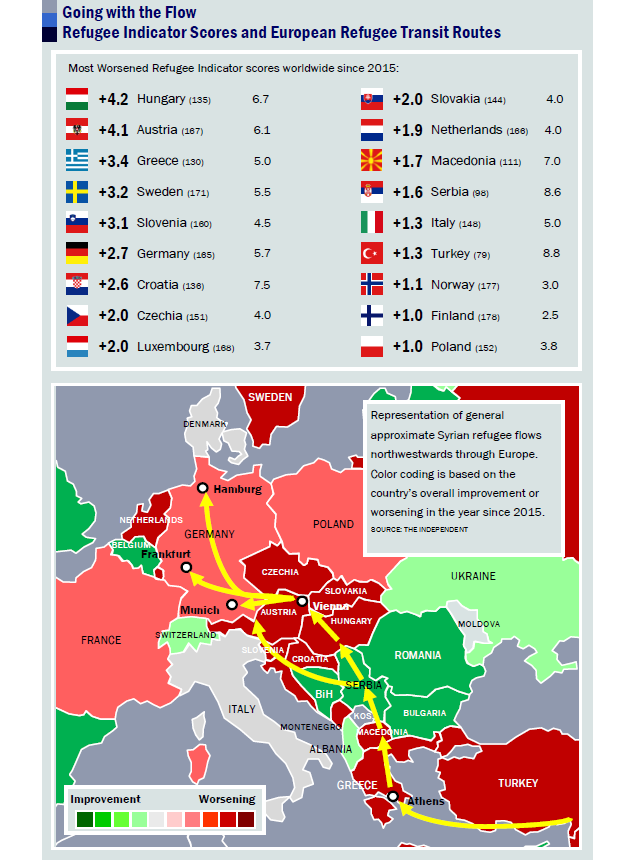

To date, thousands of Syrians have made treacherous and uncertain journeys across land and sea to the relative safety of Europe, and it is likely that many more will continue to do so. The countries of Europe – particularly those situated on a trajectory between Turkey and Germany and Scandinavia – have found themselves overwhelmed by the influx, and have responded to these pressures with attempts to close previously open borders. At the same time, ultra-nationalistic, right-wing, anti-immigrant political parties in multiple countries across the continent have taken the opportunity to politically manipulate the crisis and further destabilize domestic politics.

Most-Worsened Country for 2016: Hungary

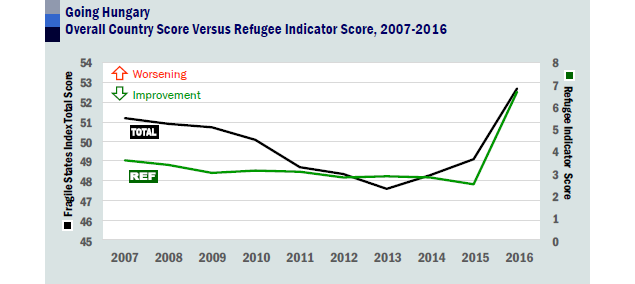

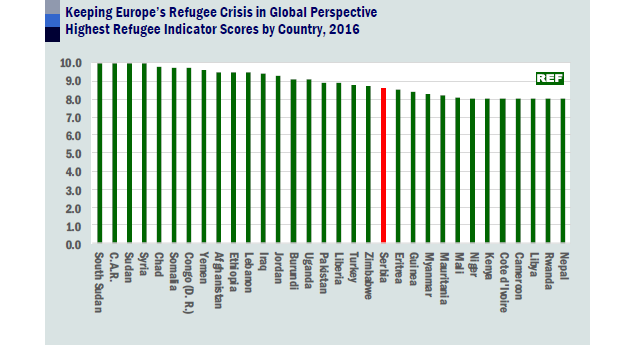

Given these spreading waves of instability, it is perhaps no surprise that the most worsened country for 2016 is European. Hungary worsened by 3.6 points on its score from 2015, its score heavily influenced by its performance on its Refugees and Human Rights indicators. Of the 20 most-worsened countries since 2015, nearly half are European: Hungary is joined by the Czech Republic, Greece, Turkey, Macedonia, Sweden, Slovakia, and Slovenia – all of which happen to lie on that same fated trajectory to northwest Europe. Notably, of all countries worldwide, the top 18 most worsened scores on the Refugees Indicator since 2015 are European. Though, on overall Refugees Indicator scores, the pressure experienced by European countries with regard to refugee flows should be placed in perspective: only two European nations, Serbia and Turkey, even rank in the top 30 for pressures from refugees, with the highest scores reserved for countries primarily in Africa and the Middle East.

But it would be way too easy to blame Hungary’s (or Europe’s) woes on refugee flows. Throughout history, many countries have been confronted with the challenge posed by an influx of desperate people fleeing en masse from war, violence, and persecution in their own fragile states. Kenya, for example, is a current example of the pressures that significant refugee inflows from another country – in this case, Somalia – can impose upon a country. Similarly, for Pakistan and its large populations of refugees fleeing war torn Afghanistan; for Lebanon, where 1 in 5 of its population are refugees from either Syria or Palestine; or for Turkey, for whom the Syrian civil war is on its doorstep. However, no one would suggest that refugee flows are the only cause of any of these countries’ current levels of fragility. Similarly, although Hungary’s policy responses to the refugee crisis have been restrictive and protectionist, this year’s worsening in Hungary is merely an accelerated trend based on largely domestic issues.

Hungary’s five year trends demonstrate a worsening in the indicators that measure Group Grievance, State Legitimacy, Human Rights, and Factionalized Elites, which suggests that many of Hungary’s pressures are home-grown. Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s ruling Fidesz government has limited the powers of judiciary and stacked it with political allies. There are allegations that a change in the electoral system allowed the party to sweep to victory again in 2014. As restrictions on the freedom of the press have increased, Hungary’s public television channels have been packed with pro-Fidesz journalists. These measures have all culminated in a rapidly shrinking space for civil society and threats to the rights and freedoms of Hungarians. It is therefore little coincidence that after Refugees, the worst indicator score for Hungary is for State Legitimacy.

Beyond Hungary, the outlook for Europe remains concerning. Though many countries in Europe have, perhaps predictably, recorded worsening in their indicator scores for Refugees, this has been accompanied by similar worsening in Group Grievance and Factionalized Elites scores, suggesting deepening rifts within society, particularly along sectarian lines. The increasing fragility in Europe is further fueled by rapidly increasing Euroscepticism, which manifested itself in last week’s “Brexit” referendum, wherein British voters elected to leave the European Union, no doubt severely undermining the political and economic alliance going forward and potentially leading to a far less cohesive Europe. Although much of the former Yugoslavia and Eastern Bloc countries have seen great improvements in the past decade, the Fragile States Index shows that much of “Old Europe” has at best stagnated, or has significantly worsened. Indeed, Greece remains the eighth most worsened country over the past decade, in no small part due to its economic woes and continued political dysfunction which saw the country as the third most worsened European country – and sixth overall – over the past year.

Nigeria and Regional Instability

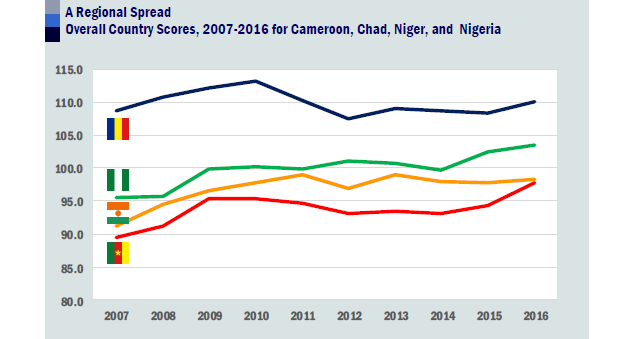

Interconnectedness and cross-border pressures have been felt significantly as a result of the civil war in Syria. However, another example of destabilizing cross-border effects can be seen clearly in the West African powerhouse nation, Nigeria. Beset by a tumultuous electoral campaign in 2015 that saw the administration of Goodluck Jonathan unseated by the return to power of Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria’s standing in the Fragile States Index has worsened, as the economy is deeply impacted by falling oil prices and the north of the country is terrorized by Boko Haram insurgency.

As with the crisis in Syria, pressures have bled across Nigeria’s borders to its neighbors. The second most worsened country in 2016 is Cameroon, which has seen a marked increase in cross-border violence perpetrated by Boko Haram – violence that has generally originated in Nigeria. These pressures have been experienced in multiple ways. Firstly, and most visibly, Boko Haram have widened their campaign beyond Nigeria’s borders and are now kidnapping and ambushing Cameroonian security forces, as well as targeting Cameroonian civilians. Cameroon is also experiencing increasing pressures from Nigerian refugees fleeing into Cameroon to escape the violence in their own country, in turn placing intense pressure on food and medical supplies in Cameroon. The World Food Programme has estimated that as many as 100,000 people find themselves displaced in Cameroon as a result of the Boko Haram-generated instability, including both Nigerian refugees and internally-displaced Cameroonians.

Niger, to Nigeria’s north, is similarly under pressure as a result of the Boko Haram insurgency. Though Niger has not worsened as much in the past year as has Cameroon, it is nevertheless still experiencing intense pressures. In late 2015, the Nigerien government declared a state of emergency in the border region of Diffa, adjacent to Nigeria, to deal with the continued cross-border attacks by Boko Haram, that has already claimed a growing number of civilian casualties. Adding further pressure on Niger – which is one of the world’s poorest countries and finds itself at the bottom of UNDP’s annual development report – it is estimated by UNHCR that in 2015 alone, 150,000 Nigerian refugees had fled across the border into Niger to escape the violence perpetrated by Boko Haram.

Notably, Chad has also seen notable worsening over the past year, however it is less clear as to how much of that worsening was contributed by the spillover from Nigeria, particularly as Chadian troops find themselves heavily involved in engaging Boko Haram, even within Nigeria’s borders. Regardless, it is clear that Cameroon and Niger – and to a lesser extent, Chad – are coming under intense pressure induced by violence and instability in its larger neighbor, demonstrating again the extensive interconnectedness evident in the Fragile States Index scores.

Most-Improved Country for 2016: Sri Lanka

Meanwhile, the most improved country in 2016, Sri Lanka, is a country that until recently was wracked by civil war and extensive violence along ethnic lines. Sri Lanka’s performance demonstrates that improvement within the Fragile States Index must be interpreted in context. The improvements in Sri Lanka should not be taken to be a wholesale endorsement of government policy or for the government’s widely-criticized strategy towards the end of the civil war, but rather a recognition that economic development, along with political stability, has improved since the conclusion of the war. Indeed, Sri Lanka’s ranking of 43rd, and its place in the “High Warning” category of the Index, cannot be ignored. Even more concerning for a post-conflict country, indicators such as Group Grievance and Factionalized Elites (along with Human Rights), which suggest deep schisms within society, remain perilously high.

Historical Trends

The 10-year trends of the Fragile States Index demonstrate a mix of near self-evident cases, as well as a number of other negative trends that bear further monitoring. The four most worsened countries over the past decade probably come as little surprise – Libya, Syria, Mali, and Yemen, which have all experienced internal conflict and strife. But the performance of some other countries that have worsened the most in the past decade should perhaps serve as a warning. South Africa, for example, long heralded as an economic engine of Africa and certainly the most developed nation on the continent, is also demonstrating significantly worsening trends in line with deepening political divisions and social unease, including increasing protests and civil disturbances. Though Eritrea’s shaky performance under the isolationist dictatorship of Isaias Afwerki may not come as much of a surprise, the significant worsening of other African countries such as Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Gambia, Djibouti, and Ghana should be cause for alarm – in particular for Ghana, which is often cited as a shining light of democracy and development in a frequently conflicted region.

At the other end of the spectrum, Moldova, as the most improved country of the last decade, is one of 23 former Eastern Bloc or post-Soviet countries to have demonstrated an improving trend. (Interestingly, the only Eastern Bloc or post-Soviet country to have worsened over the past 10 years is Ukraine, which worsened largely as a result of its conflict with Russia that involved its larger neighbor occupying the Ukrainian region of Crimea). The second most improved country of the past decade is Cuba, which despite continued pressures as regards human rights, has nevertheless seen improvements under the leadership of Raul Castro, a trend that is likely to be even more pronounced when the recent warming of relations with the United States is captured by the 2017 Fragile States Index.

* * *

In 2016, 78 countries improved upon their previous year’s score, while 77 countries recorded worsened scores. In addition, a further 23 countries recorded either no change or a very marginal movement. This is a reversal of a positive trend last year that saw 108 countries improve on the previous year, and only 52 worsen. Over the decade, 91 countries have improved upon their position of a decade ago, while 70 countries have worsened over the same period. Finally, a further 16 countries recorded insignificant changes over the period.

There is much to be concerned about in the findings of the 2016 Fragile States Index, as Europe confronts a refugee crisis of massive proportions and increasing political illiberalism, as civil wars rage on in Syria, Yemen, and Libya, and as insurgents continue to terrorize civilian populations such as Boko Haram in Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad and Daesh throughout parts of the Middle East and North Africa. The opening six months of 2016 suggest justified pessimism for the outlook for much of the world as continuing crises show little indication of resolution, and new threats begin to arise. Nevertheless, despite the doom and gloom that tends to occupy the current news cycle, countries like Moldova, Cuba, Turkmenistan, Belarus, the Seychelles, and Barbados demonstrate that away from the headlines, there are plenty of countries that are quietly making long-term progress. It is that steady, largely unsung progress that should give us hope that for every crisis wracked country we read of in the headlines, there is another country that is moving well in the right direction.