BY KATIE CORNELIUS

After two days of voting in the most closely contested presidential election in Nigeria’s history, Attahiru Jega, the chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), announced the final electoral results in favor of opposition candidate and former military ruler Muhammadu Buhari. Buhari’s victory marks a historic occasion for the country considering an opposition candidate has never before defeated the ruling party in a presidential election. At last count, Buhari claimed 15.4 million votes over incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan’s 13.3 million.

Despite some technical issues with electronic card readers as well as insecurity arising from the sporadic targeting of voters by Boko Haram militants in the Northeast, the National Democratic Institute’s international elections observers overall hailed the presidential election as smooth and orderly in a preliminary statement offered on March 30. Allaying fears that internally displaced persons (IDPs) would be unable to vote, Aljazeera reported that thousands of IDPs in the Northeast ignored threats of violence from Boko Haram and voted in their internal refugee camps. Only limited violent protests broke out in Rivers and Kaduna after unsubstantiated allegations emerged of vote rigging.

The international community had every reason to believe they would see increased violence in Nigeria in the days immediately before and after the 2015 elections compared with the same period in 2011. While protests, thuggery, and violence divided Nigeria along ethnic and religious lines in the April 2011 elections, this time around the country faced an even more polarized political environment between the ruling and opposition parties as well as a worsening security situation in the North from the Boko Haram insurgency.

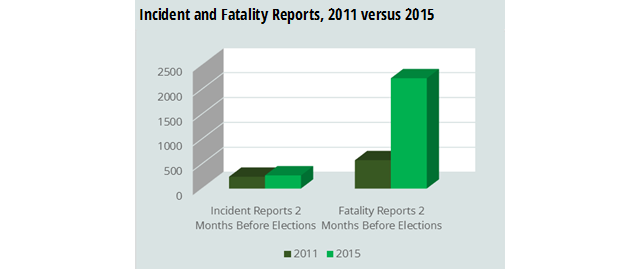

Looking back at the two month pre-election period in 2011, 237 instances of insecurity and 569 fatalities were reported while an additional 800 people were killed in immediate post-election violence. The comparative pre-election period in 2015 saw 264 instances of insecurity and 2215 fatalities. Examining these numbers in the context of increased pre-election tension and insecurity in 2015, observers would naturally expect post-election violence to be even bloodier than it was four years ago.

Despite doomsday predictions that the 2015 presidential elections would result in a fresh wave of violence, so far this year’s elections results have been met largely with peaceful acceptance. One reason for this outcome can be attributed to an unprecedented move by Goodluck Jonathan to concede defeat and congratulate Muhammadu Buhari on his win before the final elections results were announced. Neither the All Progressives Congress (APC) nor the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) were expected to accept the election as legitimate unless the results were in their candidate’s favor. However, with one brief phone call to the president-elect, President Jonathan may very well have pulled Nigeria back from the brink of conflict and opened up the possibility for Nigeria to witness its first peaceful democratic transition. With a political stalemate largely out of the question, Nigerians can now focus on their country’s budding democracy. The ability for Nigeria to maintain peace in the post-election period has huge implications for the whole West African region. If Nigerians can collectively take the driver’s seat and steer the trajectory of their country towards democracy, they will serve as a model to other countries for what can be achieved with credible elections.

While Nigerians have much to celebrate with the outcome of the presidential elections, the April 11 gubernatorial elections remain both an opportunity and a test for Nigeria’s fragile democracy. To Nigerian nationals and outside observers alike, these elections are equally, if not more, important than the presidential vote. Just days after losing the presidency and a senate majority, Dayo Johnson of Vanguard discovered that the ruling PDP has been losing high-level party officials in Ondo, Oyo and Adamawa States as they defected to the party-elect APC. With the PDP on the verge of folding in on itself, the upcoming gubernatorial elections could determine the party’s future in Nigeria and possibly leave the country again without a strong opposition to the ruling power.

According to Darren Kew, an associate professor on conflict resolution at University of Massachusetts in Boston, the fact that the APC is made up of elements of the old PDP could present a real problem if old patterns were to reassert themselves. The scenario Kew refers to in his interview with Morgan Winsor for International Business Times is the possibility that once the APC takes control, the party will succumb to Nigeria’s old vice: corruption. In addition, violence could rise in the country if locals do not accept a change in guard. Since Nigerian governors are in charge of allocating federal revenue, the end of PDP rule at the national and state level may come with high financial stakes.

Though it remains to be seen how Nigeria’s gubernatorial elections will turn out, observers ought to remain hopeful that Nigerians will once again rise to the task of demanding change at the polling stations. If voters turn out en masse with the same confidence, commitment, and patience that they had in the presidential elections and those results are accepted as fair by all running candidates, then Nigeria’s move towards democracy will be even more solidified.