BY NATE HAKEN

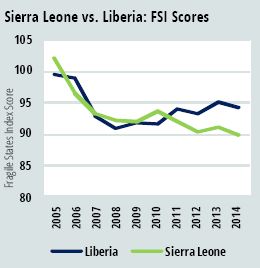

Many truisms about peace-building incline towards pessimism. There is a “vicious cycle,” a “conflict trap,” “unintended consequences,” the problem of “political will,” and a slew of transnational “exogenous pressures” beyond the sphere of anyone’s control. Certainly, the Fragile States Index (FSI) is often perceived as a buffet of bad news stories and cautionary tales with the same sorry countries at the top of the list year after year. But there are also cases of sustained and steady progress that give occasion for hope. Liberia and Sierra Leone in West Africa offer two lessons for peace-builders working for lasting change.

The first lesson relates to myopia. Peace-building is a long term proposition. It has taken ten years for Sierra Leone to move out of the Alert category, where it was in the FSI 2005. If people are expecting fast results, they are bound to be disappointed. It takes a generation. The second lesson relates to tunnel vision. Effective peace-building takes a regional perspective because a state may be unitary in theory but the neighborhood plays a major role in its trajectory. If these two lessons are internalized by those with a stake in peace and security in both public and private sectors, it will help peace-building actors to be more successful in promoting sustainable human security. Ten years from now, countries like Guinea and Zimbabwe could be emerging out of the Alert zone as well.

The tight correlation between improvements in Liberia and in Sierra Leone is not surprising when you consider how interwoven their histories are. When the FSI was first being produced in 2005, both countries were just coming out of a decade of civil war. In Sierra Leone, the war was between the Charles Taylor-backed Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and the government forces. It was triggered by economic mismanagement and political disgruntlement, fueled by blood diamonds and military coups. About half of the population was displaced and thousands were subjected to sexual assault and the amputation of their limbs. ECOWAS troops intervened in 1998 followed by UN troops in 1999. In 2001, the rebels began to disarm. Meanwhile, in Liberia, there were two civil wars, the first one from 1989-1996 between the Armed forces of Liberia and rebel groups led by Charles Taylor and Prince Johnson. The rebels ultimately defeated the government forces and Charles Taylor became president in 1997. Subsequently, a new constellation of rebels emerged, backed by Sierra Leone and Guinea. In 2003, a ceasefire was signed, ECOWAS peacekeepers from Nigeria were deployed, and Charles Taylor resigned.

During the fifteen-year period of brutal violence spreading through West Africa in the 1990s and early 2000s, the lessons people often took were that state failure is intractable and that ceasefires don’t hold. Violence mutates and evolves, but never gets resolved in a lasting way. Conflict management is the best we can hope for. Even that may be Pollyannaish, considering the hard realities and imperatives of warlordism in states that simply cannot manage the social, economic, and political pressures on society in a legitimate, representative, and professional way. Conflicts only end when they burn out. Then they simmer. When the Sierra Leonean rebels disarmed in 2001 and Charles Taylor stepped down as president of Liberia in 2003, it was not a foregone conclusion that war would not break out again. There had been so many twists and turns along the way. Why should this time be any different? And yet, looking back across ten years of data, it is clear that from the mid-2000s on, the region has become much less fragile. Granted, in 2010 Liberia moved up a little, in part due to the cross-border issues with Cote d’Ivoire in the wake of election violence and the toppling of President Laurent Gbagbo. But in general, the trend was and is overwhelmingly positive. The hard work of peacekeeping was done by regional and international actors. But the harder work of peace-building was done at the community, county, and national levels by those with a stake in peace.

An index, which by definition is essentially an average of averages, is necessarily subject to caveat and qualification when using it to draw conclusions about such complex issues as regional, inter-state, cross-border, intra-state, and localized conflict. But in this case the FSI does illustrate how long it takes to move a country safely out of the Alert zone: a generation. The cases of Liberia and Sierra Leone illustrate how closely knit neighboring countries can be. An unstable Liberia played a destabilizing role in Sierra Leone. Conversely, both countries stabilized together. When peacekeepers deployed in southern Sierra Leone in 2001, Charles Taylor lost control over the diamond industry there, weakening his hold on power in neighboring Liberia, setting the stage for his resignation.

Political leadership and the security services can only do so much. Ensuring that the positive trajectory continues is now in the hands of civil society. But businesses also have a huge stake in peace. According to World Bank data, after a decade of economic stagnation, Sierra Leone’s GDP per capita turned around in 2000, more than tripling over the next ten years. The same thing happened in Liberia where the GDP per capita has more than tripled since Charles Taylor resigned in 2003.

If the success in Liberia and Sierra Leone is to be sustained and replicated, it will take both public and private sectors at every level, understanding that all have a stake in peace and must therefore play their part. Through early warning, conflict sensitive development, peace messaging, capacity building, and multi-stakeholder collaboration, fragile states across the world can become more peaceful and more prosperous. Peace-building is not binomial. One is never finished building peace in a country. When successful, peace-building, as its name suggests, is a process that just keeps building upon itself in a never-ending exercise of constant improvement.