BY KRISTA HENDRY

The Fund for Peace Commentary

This paper examines issues related to ensuring greater site and community security through collaborative efforts, focusing on the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (VPs). It provides background on the VPs for those less aware of the initiative. It then discusses company and non-governmental organizations developing partnerships, followed by a discussion on the need to include governments in the collaboration for long-term success. It closes with a discussion of how the VPs, as both a framework and an opportunity for cross-sectoral collaboration, can be a key risk management tool for mining companies.

Introduction

Mining companies are an essential part of creating sustainable societies – which requires both economic development and increased human security. They provide infrastructure development outside their immediate operations and support local economies beyond direct employment. When operating in tense social and political environments, however, mining companies can easily be seen as part of the problem instead of the solution. Companies need partners to operate effectively in areas lacking strong government institutions and a respect for the rule of law. To be effective, partners need to share a common goal or goals and have a framework by which they agree to partner.

Back in 2001, representatives of companies, governments, and NGOs (non-governmental organizations) came together and created an initiative known as the Voluntary Principles on Security & Human Rights. The initiative was designed to facilitate the ability of the three pillars, as they became known, to be able to work together to address some of the major challenges companies were facing in weak and poorly governed areas. It also sought to address a growing concern that companies’ operations were negatively impacting the human rights of neighboring communities, thus negating the positive economic impact they were having.

Voluntary Principles

The Voluntary Principles, or VPs as they are often referred, is several different things, and often seen as confusing or even daunting to someone looking at them for the first time. The VPs starts with the document that is at its core – a set of principles agreed to by the participants that lays out several key elements to an effective and appropriate security policy and program. For most companies, particularly ones operating in conflict-affected areas, a cursory review will reveal that the company is already doing quite a bit covered by the VPs. A gap analysis can fairly quickly reveal areas of improvement and help a company develop a plan to improve their ability to maintain high security while ensuring they have a net positive impact on the communities – with a goal of contributing to greater sustainable security.

The main elements that are covered in the VPs are doing an appropriate risk assessment, managing relations with private security, and managing relations with public security. Included in these areas is guidance on training, documenting, investigating, and reporting. One of the most important things about the VPs has been how over time they have changed the thinking and rhetoric related to site security to recognize that security must be about both the company and the community, not the company from the community.

There are a couple tools available for those wanting to understand what implementation of the VPs entails. The Implementation Guidance Tool, available at www.voluntaryprinciples.org, is a fairly in-depth tool related to each of the areas described earlier. While its size might initially make it look daunting, it is only so large should companies need further drill-down guidance. As mentioned earlier, companies will often find they already have some things in place and can use the tool as a way to identify areas of improvement.

The VPs is not only a framework that can be implemented by companies, it is also an international initiative guided by a Steering Committee that meets regularly to support efforts at awareness raising and national-level implementation. Companies, NGOs, and governments formally apply to join the process and the newly formed Voluntary Principles Association (VPA). The VPA is meant to help ensure that the three pillars are able to work together at the international level and tie this work back to both the national and the project levels, as briefly described in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Levels of VPs Implementation

Many companies choose to implement the VPs at their projects without joining the international initiative. For some smaller companies, this may make a great deal of sense as the absorptive capacity to join another initiative may be too low. A cost-benefit analysis can be done by a company to ascertain if joining the international initiative is worthwhile.

On the benefit side, the international level is a forum for networking and learning and there is increased acceptance a company is implementing the VPs if they are part of the international level, which can increase their reputation and reduce risk should an incident occur. On the cost side, there is the time and expenses involved, including annual dues, as well as an increased exposure, but this exposure can be positive as well as negative. If a company is carrying a risk of an incident at any of its sites, it could face exposure at any time. It is better to have an existing network to reach out to in case an incident occurs instead of waiting until something happens.

One of the greatest risks for companies operating in weak and ungoverned areas is that their presence most likely brings with it an increase in public security. Depending on the country, these forces may be poorly trained, poorly equipped, and poorly paid. Indeed, in some of the harshest places, the human rights of the public security forces themselves may be abused, leading them to be more likely to abuse those in the communities. Understanding not only the needs of the companies and the communities, but also of the forces themselves, was one of the driving reasons why topics such as equipment transfers were included in the VPs.

The VPs do not state that there can be no equipment transfers. In recognition that in some areas these are necessary to maintain security, there is merely guidance on them being well documented and as transparent as possible (recognizing security limitations). Suggested in the VPs and considered best practice, companies are asked to secure a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with public security forces. In a country where this has not been undertaken before, this can be a very lengthy process – but even documenting the discussions related to same is considered implementation of the VPs. These conversations – which must occur at many different levels from federal to local to ensure buy-in at all levels – provide a great opportunity to discuss areas of concern, which may well be shared by the leaders of the forces. If the forces are treated with respect, then what may seem a daunting task can actually bring a lot of return. But starting that conversation is difficult, and for security managers on the ground it can be a useful tool to point to the formal participation of the company in the international process as to why s/he needs to work on a MOU.

Additionally, if the host government can be brought into the conversation at the national level, it can – in some cases – be helpful to point to the government’s involvement as demonstrating it should be of importance to the security forces as well.

One of the things that the VPs recognizes best is that every country, indeed every site, has unique challenges. There is no way to develop a roadmap for VPs implementation that would be appropriate or effective at every site. This is why the VPs begins with the risk assessment process. This process guides implementation – i.e. selection of priority sites for implementation; identification of what needs to be codified by the company versus what already exists in national law; and highlights areas of needed improvement. Implementing the VPs gives guidance to a company on drafting human rights policies, creating assessment capabilities related to security and human rights, undertaking conflict and human rights assessments, and developing training materials.

Partnering with NGOs

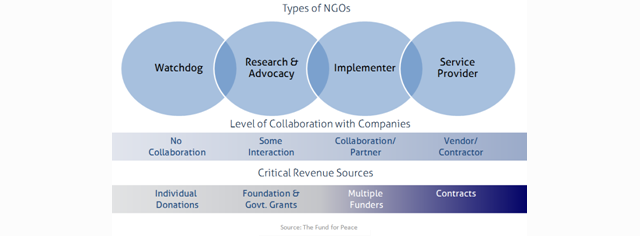

The VPs also provides the opportunity to partner with NGOs on areas of common interest and concern. One of the first things to understand is the spectrum of NGOs. Referring to the continuum shown in Figure 2, there is a spectrum of NGOs beginning with the ones on the far left, who typically use name-and-shame and campaign tactics (and perhaps even lawsuits). These NGOs have been an important contributor to why we have progressed as far as we have, by forcing some companies to the discussion table. Over time, however, we are recognizing that collaboration on important issues and being concerned about the security of the communities is just good business practice. This is allowing the NGOs in the Implementation space to proliferate.

Figure 2: The NGO Continuum

Groups like The Fund for Peace, International Alert, and others have long had programs working on the intersection of economic development and increased human security. Our work falls between Research and Advocacy and Implementation. We provide a different perspective than someone internal to a company or even external consultants or humanitarian or human rights NGOs. But we understand that there are hurdles to get by before we can cooperate more fully.

Companies may have been the target of name-and-shame campaigns in the past and may have a blanket “unspoken” policy of not working with NGOs, or at least a deep hesitation, as a result. Companies can also have concerns about how this would be viewed by the local or national government, depending on the location. And there could be security concerns related to having an NGO visit a site. All of these are valid issues but ones that can be addressed through taking the time to build trust and knowledge about each other. Some companies have included NGOs in their own internal management trainings so the NGO can better understand the company and its culture.

Implementing NGOs, however, are not the same as Service Providers. Service Providers are usually more comfortable for companies to work with, because they work on contract and are more likely to include people who have come from industry. Developing a contractual relationship is relatively straight-forward and systems exist to manage that process.

Implementing NGOs also bring valuable experience, but they work better with a company if the two create a true partnership and collaborate on the design and implementation of projects and programs. It usually takes more time to develop a partnership and trust than it does to create a contractual relationship. To work together, given their varying internal systems and controls, NGOs and companies both may need to be flexible as to the type and format of the relationship.

There is also the issue of the level of the relationships. If the trust has been built at the international level – i.e. with headquarters – there should be equal attention given to building the relationship at the local (site or national) level. This can also work in the reverse direction should a site build the initial relationship and then there is an attempt to make it an international relationship.

Building local level buy-in for the principles, the process and the partners is critical to success. As with any effort, no one likes an edict coming from above and, even worse, from outside, without knowing that they were a part of the initial design. Involving site-level staff in discussions about initiatives like the Voluntary Principles as early as possible can be the difference between success and issues later.

Collaboration with Governments

Governments make up the third pillar of the VPs and, like NGOs and companies, are also not homogenous. Governments can be home, host or a combination of both. The latter bring countries which have both foreign companies operating within their borders but also national companies operating overseas. Governments can also be federal, state, or local. And when talking about government representatives we often don’t distinguish between elected officials and civil servants, but this is a distinction that greatly changes the nature of the relationships.

At the international level of the VPs, home governments are encouraged to use their diplomatic resources to build awareness and encourage adoption of the VPs by host governments. Within a host country, governments are asked to use their resources to help identify ways to have dialogue about sensitive issues, such as security and human rights, with their government counterparts. This can be of critical support to the companies’ abilities to develop MOUs, as previously described as best practice. At this level as well, we are increasingly exploring how different government agencies can support important security sector reform in host countries, helping to decrease the risks to companies and communities that come when public security is not properly trained or equipped.

Governments are extremely vital in all of this. Sustainable security will not be possible unless the social contract between the people and their government is strengthened. For mining companies operating in rural and impoverished areas where government capacity is low or missing altogether, they are often in a position in which they need to provide immediate services and infrastructure. Over time, however, it is critical that companies are able to bring in government, develop its capacity, so they can return to their appropriate role as an economic engine and the people rely on their government for the services they more appropriately should provide. While ideal, this can take a very long time; NGOs can be an important bridge and partner in helping to support that development.

Conclusions

Collaboration between companies, NGOs, and governments on issues as important as human security and company-community engagement is as difficult as it is necessary. The challenges that companies and communities face in high-risk areas can only be solved through multi-sectoral engagement. The last decade has seen a real change in our ability to collaborate in constructive ways and looking forward this trend seems to be growing.

The VPs is only one of many initiatives, but it is set up to tackle a major issue that requires real collaboration across sectors – how to ensure greater community security while maintaining the security of a company’s property, employees, and assets. No one sector alone can work successfully on increasing the human rights performance of public or private security forces.

The VPs are an important risk management tool for all three pillars and at all levels – project, national, and international. If done in true collaboration, while exploring ways to bring the communities and security forces into the conversation, we can build the real trust and respect needed across all sectors to face the challenges. Industry and impacted communities have been facing them alone for far too long.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the work of the other VPs participants in developing the learning included in this document. As this document is based on the practical application of the VPs in partnership with many companies, NGOs, and governments over the past decade, it is impossible to give direct attribution.

Not only participants but also observers, specifically the International Finance Group, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the International Committee on Mining and Minerals, and IPIECA, greatly supported the creation of the Implementation Guidance Tools.

References